THE GUNSHOT TREATY

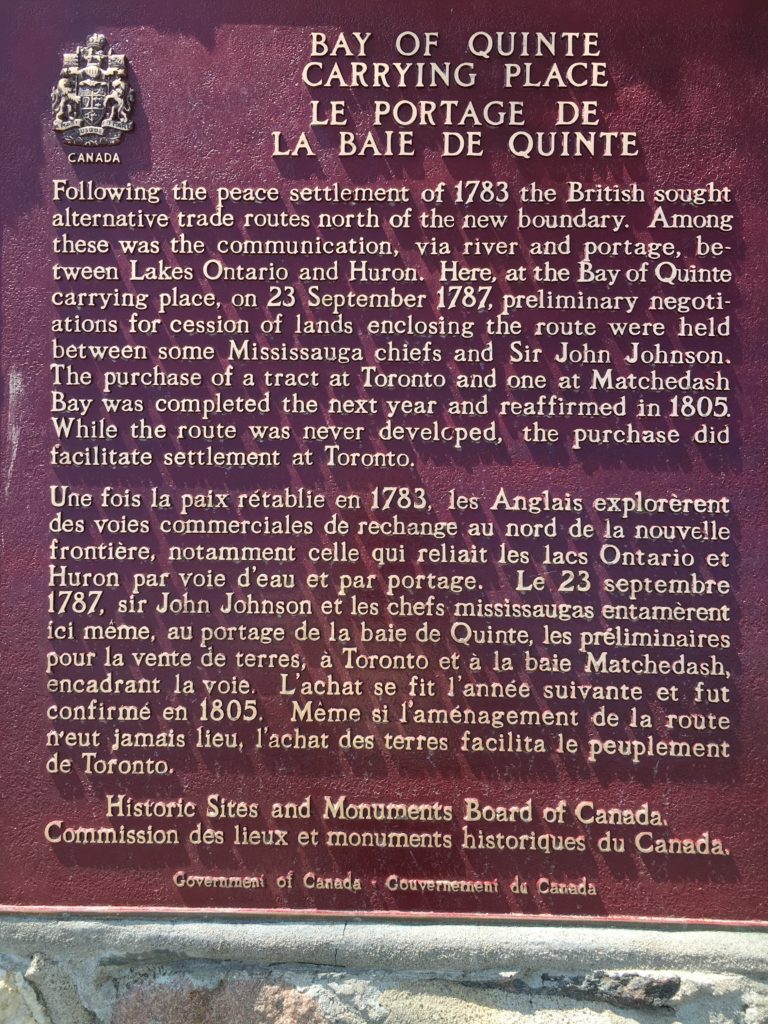

It is easy to pass by the stone cairn at the stoplight in the village of Carrying Place bordering Prince Edward County and Quinte West. But the cairn at this busy intersection of Highway 33 and Portage Road marks a crossroads in history. On September 23, 1787 hundreds of Indigenous Peoples from the Mississauga Nation met with representatives of King George III to negotiate an historic land deal known as The Gunshot Treaty.

The treaty was spurred by the urgent British need to find land for thousands of United Empire Loyalists looking to re-settle after their flight from their homes in The United States during and after the American Revolution. The Gunshot Treaty was one of a number of hastily arranged negotiations with Aboriginal peoples along Lake Ontario, drawn up to secure title to land for survey and settlement, and to develop alternative water routes for commercial travel and military use. The Gunshot Treaty would become the 13th in this series of land negotiations.

Carrying Place has always been a significant site. Long before French explorer Samuel de Champlain journeyed through the area, and before the fur traders and missionaries of the 17th century, Indigenous Peoples portaged their vessels across a narrow neck of marshland to the gentler waters of the bay that would one day be named Quinte. The Mississauga called this place “de-ga-bun-wa-kwa” meaning “I pick up my canoe.” Europeans called it Carrying Place and the name stuck. In the decades which followed, the site became a major commercial corridor connected by a stagecoach service and later, the Murray Canal. But in the 1780s it was simply a well – known landmark ideally suited as a gathering place for treaty talks.

Treaty discussions were guided by an over-arching British approach dictated by The Royal Proclamation of 1763, which attempted to standardize administrative policies in acquiring land from Indigenous Peoples in North America. Implicit in the policy was the notion that they retained traditional hunting and fishing rights, and that settlement lands had to be secured from them through purchase agreements. Although the policy fell short of recognizing Aboriginal ownership of the land, it was for its time a surprisingly enlightened diplomatic departure from the usual land grabs by Europeans claiming title by simple discovery or conquest. Despite the good intentions, The Gunshot Treaty and its sister agreements proved to be both landmarks and landmines in relations with First Nations.

The September 1787 land talks were first experiments in cross-cultural communications. Despite the presence of an interpreter, the British desire to firmly secure land title was foreign to a communal society where individual ownership was unknown. The translation of words such as “surrender” of land title was more broadly understood as “shared” in the Ojibway language. The retention of the right to hunt, fish and travel undisturbed throughout the waterways of the region with yearly ceremonies and gifts from the British sounded like an annual rental of land rights rather than a purchase. And because it was not possible to complete surveys until a treaty was finalized, the description of the lands covered by the treaty were left blank.

The Gunshot Treaty took its name from its terms. It covered the lands as far as a gunshot could be heard on a clear day. In time, this came to mean to the British all the lands in present day Eastern Ontario and beyond. In return, First Nations received a payment of approximately 2,000 pounds, and goods such as muskets, ammunition, tobacco and clothing. The agreement was to last as long as “you see the sun in the sky, as the rivers flow, and the grass grows.” Even today, The Gunshot Treaty is a bewildering read, and remains a contentious issue despite repeated efforts to clarify its terms.

In a twist of history, this early treaty and other land claims reverberated across the country in 1969 when the Nisga’a people of northern British Columbia took the federal government to the Supreme Court to press for settlement of their land claim. They argued they had never surrendered their land through a treaty or been defeated by conquest. And they claimed that even the earliest treaties – like The Gunshot Treaty – clearly indicated the British government recognized that Aboriginal Peoples had at least some traditional rights to the land, and this territory had to be purchased to secure title.

The Nisga’a didn’t win their case. But they didn’t lose it either. The split decision of The Supreme Court was enough to force the federal government to begin to negotiate land claims. After decades of talks, the federal and provincial governments signed a final settlement with the Nisga’a in May 2000 that featured a cash payment, self-government, and ownership of land and resources including timber, salmon stocks, and sub – surface resources.

Land claims are now a fixture of government policies. They remain slow, complicated processes – and highlight an often-painful history. But early treaties like The Gunshot Treaty set important legal precedents. They continue to be re-negotiated to this day. Their resolution is part of a new path forward towards reconciliation.

Perhaps one day The Gunshot Treaty cairn can be moved from its current site at the stoplight in Carrying Place to a safer and more prominent area like The Murray Canal so this forgotten history can be better explained and understood by a new generation.