The History Moments are a series of two-minute “popular history” segments on local history themes, which play before movies at The Regent Theatre.

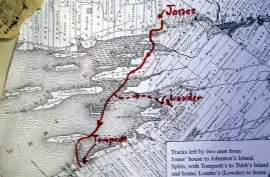

Twelve more vignettes on the rich history of Prince Edward County will be premiered at a free gala event open to the public. This year’s series includes stories on temperance advocate Letitia Youmans, prominent Loyalist settler Peter VanAlstine, The Quakers, Mohawk settlement on the Bay of Quinte, Sir Thomas Picton, the old Danforth Road linking York (Toronto) with Kingston, the Glenora Ferry, and others. One of our sponsors, the Black Prince Winery, will be providing complimentary wine at a reception which follows the premiere.

Please plan to attend this celebration of Prince Edward County’s history!