George Lowder, aged 23, died first. But his fellow prisoner, Joseph Thomset, a 35-year old fisherman, struggled for a full fourteen minutes on the hangman’s noose on the early morning of June 10,1884.

Sentenced to hang at the Picton gaol for a botched robbery outside of Bloomfield that left one man murdered in December 1883, Lowder and Thomset maintained their innocence to the end. But were they innocent? Many local residents thought so and unsuccessfully petitioned the courts and Prime Minister John A. Macdonald for clemency. It remains the most celebrated court case in the history of Prince Edward County.

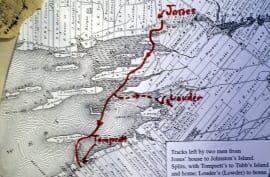

The fate of Lowder and Thompset hinged on the evidence of the boots they wore and the tracks in the snow that led a posse of local men to their homes.

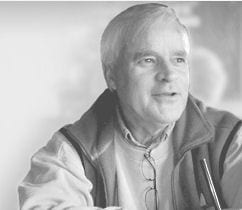

“Well the tracks are very important because that’s how they think they got the two men who committed the crime.” says Judge Robert Sharpe, a Picton native who now serves on the Ontario Court of Appeal in Toronto. Sharpe is writing a book on the 1884 trial.

“There were clearly tracks leading from the house going in the direction of West Lake and certainly tracks found around the homes of these two men. No one was actually able to trace the tracks all the way from the farmhouse to the two different homes, but they could find tracks along the way.

There was one pair of boots that had a somewhat distinctive bottom called a “patch bottom” and the people that did the tracking thought that they could tell if it was this particular pair of boots that left the tracks and that pair of boots was found in the home of one of the two men.”

And yet, there were many inconsistencies in the trial testimony that might have saved the men in another age. A local boot maker testified that the “patch bottom” boot was very popular in The County and the size – 8 1/2 -was also the most common size. Key witnesses such as Mr. and Mrs. Jones, Quaker farmers who defended their home against the robbers, were uncertain about identifying Lowder and Thompset as the men who had entered their house. Farmer Jones thought one of the men was older and had a limping gait.

“For some reason,” says Judge Sharpe, “nothing much was made of this but it occurred to me that this might support the local feeling at the time that maybe it was the father John Lowder and not his son George who was involved in the crime because as Mr. Jones described the man running off, he said he had a kind of ungainly gait; he was running with a bit of difficulty. Now you’d think that would suggest perhaps an older man who was having a little bit of difficulty running. But somehow that issue didn’t get exploited at the trial, and there were some very fine lawyers at this trial so it’s hard to second-guess them at this distance. But it occurred to me that that was something that was potentially quite important.”

Judge Sharpe is skeptical of the conviction of George Lowder.

“We know that Joseph Thompset was in his early thirties,” he says. “He was a fisherman and he fished in partnership with George Lowder’s father, John Lowder. He lived near West Lake with his wife and one child. In the case of George Lowder, it was a family of several children. He was the second youngest and he was a mason by trade. He was much younger. He was in his early twenties. Thompset had had encounters with authorities before, and had been charged with minor offences before. Lowder had a completely clean record.”

In the charged atmosphere that swept through the County during the months following the crime, it was difficult for the two accused men to receive a fair trial. They weren’t allowed to testify in their own defence. And in the court of public opinion, they were guilty as hell.

“The atmosphere was quite amazing,” states Judge Sharpe,” because this was a huge event in the life of the town. There was a large crowd of people. The hotels were full. It was very difficult to get into the courtroom. The courtroom holds a lot of people, but there was a lineup of people who could not get in. The people in the courtroom were we know from the trial records, and from a letter from a prominent lawyer written after the trial, extremely unruly. And they would applaud every time the prosecution made a point and jeer every time the defence tried to score a point. And at a couple of points the trial judge had to clear the courtroom as he felt the crowd was so unruly and so disrespectful of the process. Clearly there were strong feelings at the time and I would say that a substantial part of this community were out for blood. They were convinced that these were the two men who had committed this crime, it was a horrific crime and they wanted blood. The mood started to shift after the verdict when some other people who were very concerned about what had happened, who had grave doubts about their guilt, tried to mobilize and they did mobilize a very long petition that was sent to cabinet, to Prime Minister Macdonald and Justice Minister Campbell to try to persuade them to commute this sentence. But they were a little too late in the case of Mr. Thompset and Mr. Lowder because they were hanged about a month after the trial.”

And so did they hang the right men back in 1884?

“There was a great deal of legal talent assembled for this trial,” Judge Sharpe says. “Judge Christopher Patterson practiced law in Picton early in his career with Philip Low and was later appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada. The crown and defence attorneys were outstanding lawyers. But in the end, it’s a very human process.”

Judge Sharpe, a member of the Ontario Court of Appeal, is the author of several books on law and legal history. Raised in Picton, he is currently completing a book on the Thomset -Lowder trial due for release in 2011.

Sharpe’s lecture reviewed the case – the crime scene and investigation of the trail of footprints in the snow that led to the two men’s houses; the evidence presented; the personalities that dominated the courtroom drama from the unruly mob who attended to the witnesses, judge, jury and lawyers; the verdict that condemned the two men to death, and the desperate effort to save the prisoners’ lives following their sentencing.