**MEDIA RELEASE**

SPRAGUE RELEASES NEW LINE OF HERITAGE CANNED GOODS

February 7, 2022

Sprague Foods of Belleville is introducing a new line of canned products showcasing the history of the canning industry of Prince Edward County, Ontario – once the centre of the industry in Canada. The new line of canned soups, peas, corn and beans features heritage labels originally designed for local companies during the heady days of the industry from 1880 until the late 1960s when the area was known as the “Garden County of Canada.” Profits from the initiative help support The Ameliasburgh Heritage Hub, a collective of heritage organizations in the village.

Sprague Foods has its own rich history. The company started in 1925 and is the sole local survivor of the dozens of canning companies that once operated in the region. The company is now in its fifth generation as a family-owned and operated local business.

“Over the decades, we have kept innovating new products to keep up with an ever-changing market,” says Keenan Sprague, a great- great – grandson of company founder, J. Grant Sprague. “This project continues that tradition of innovation. These vintage labels are beautiful and remind us of a time when local vegetable canners and farmers were thriving. Profits from the project support the work of several local heritage organizations to celebrate and preserve this history. We believe this is a way for consumers to purchase an everyday quality product while learning more about an industry that once meant everything to Prince Edward County.”

The Ameliasburgh Heritage Hub is a newly – formed alliance of community organizations in the village of Ameliasburgh including the Marilyn Adams Genealogical Research Centre (operated by the 7th Town Historical Society), the Ameliasburgh Heritage Village (one of the five County museums), History Lives Here Inc., and the Quinte Educational Museum and Archives.

“We’re very excited about the Hub project,” says Janet Comeau of the 7th Town Historical Society. “Over the last year, we and our heritage neighbours have come together in a collective effort to promote the history that is all around us. Partnering with a local business like Sprague Foods to create consumer products which showcase the past, is a novel way of engaging residents and visitors in community history while raising funds to support our efforts.”

The project features heritage labels from several Prince Edward County canning companies including the Lion Brand produce of canning pioneer, Wellington Boulter, the father of the canning industry in Canada, and other long-established companies like the Sunset Brand produce of John W. Hyatt and Sons. Each product includes a short history about the original canning business.

A launch event at the 7th Town Historical Society office is planned for Tuesday, February 22nd, 2022 starting at 9AM.

The sale of these goods will be limited to the local Bay of Quinte area and adjacent counties.

Sprague Foods

385 College St.

Belleville, ON K8N 5S7

www.spraguefoods.com

Tel: 613-966-1200

7th Town Historical Society

528 County Road 19

Ameliasburgh, ON K0K 1A0

info@seventhtownresearch.com

Tel: 613 – 967- 6291

The Murray Canal, built between 1882 – 1889, provided an alternative shipping route around the treacherous shoals of Prince Edward County in the great days of sail and steam. And after nearly a decade of heated community debate, Prince Edward County’s own railway line was completed in 1879 with the tracks ending at what is now Lake Street on the western edge of downtown Picton.

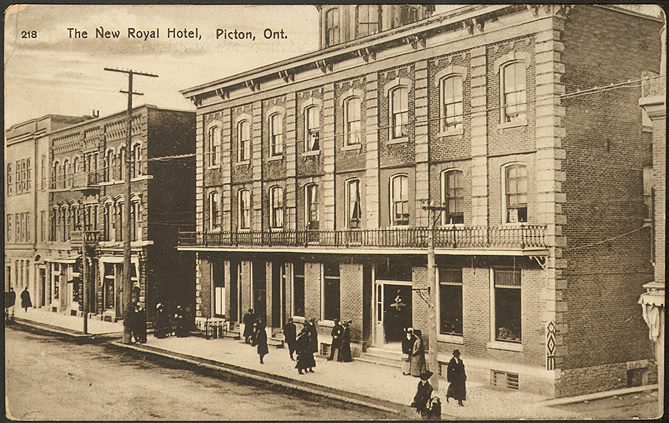

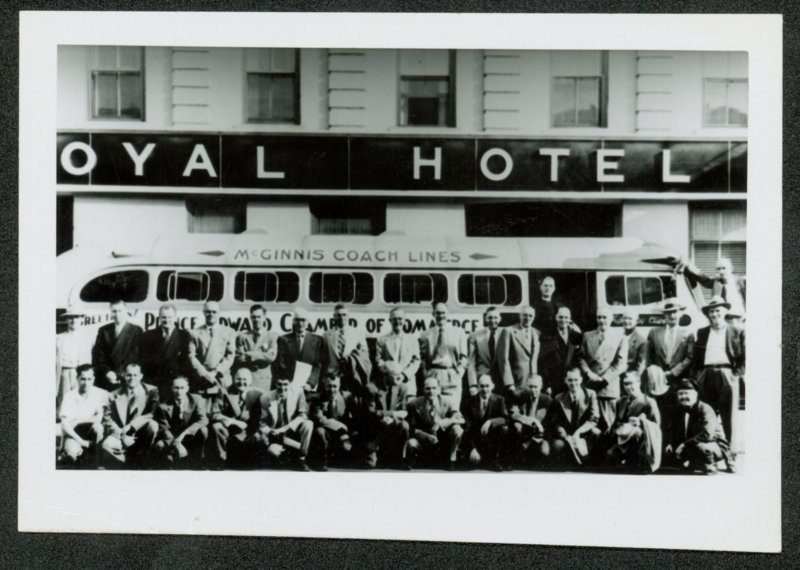

The Murray Canal, built between 1882 – 1889, provided an alternative shipping route around the treacherous shoals of Prince Edward County in the great days of sail and steam. And after nearly a decade of heated community debate, Prince Edward County’s own railway line was completed in 1879 with the tracks ending at what is now Lake Street on the western edge of downtown Picton. Friday and Saturday nights brought farmers to town to buy their groceries and other supplies, and to spend their hard-earned dollars on a rare luxury like a dinner at The Royal. The insatiable demand for food during two world wars brought boom times, which offset the ten lost years of the Great Depression. The construction of Camp Picton, a Commonwealth air training facility built in 1939, swelled the town’s population with a substantive military presence. These were the great days of The Royal as the hotel hosted dinners and dances, military balls, birthdays, weddings and anniversaries, election nights, and served as a meeting space for service clubs, warden’s banquets, and other community events.

Friday and Saturday nights brought farmers to town to buy their groceries and other supplies, and to spend their hard-earned dollars on a rare luxury like a dinner at The Royal. The insatiable demand for food during two world wars brought boom times, which offset the ten lost years of the Great Depression. The construction of Camp Picton, a Commonwealth air training facility built in 1939, swelled the town’s population with a substantive military presence. These were the great days of The Royal as the hotel hosted dinners and dances, military balls, birthdays, weddings and anniversaries, election nights, and served as a meeting space for service clubs, warden’s banquets, and other community events.